Once the grapes reach the wine-presses, but before they are unloaded from the lorry, they are weighed by inspectors from the Consejo Regulador in order to verify that they do not exceed the production limits fixed for each vineyard every year. In addition to weighing the harvest, a representative sample of the whole load is taken in order to analyse certain parameters concerning the degree of ripeness and healthiness of the grapes.

The grapes are then generally unloaded into a reception hopper fitted with a continuous screw system that carries the grapes to the first operating unit, usually a crusher or a combined de-stemmer and crusher. The aim of the crushing process is to facilitate the extraction of must under the effect of pressure. The crushing process breaks the skin of the grape, releasing a quantity of grape-juice (must) derived from the fruit pulp.

De-stemming, or removal of the grape stalks, is an optional procedure which may be partially or totally carried out prior to crushing. When the grape-stalks are broken up they release certain herbaceous compounds and tannins which have a detrimental effect on the quality of the wine. The presence of a certain quantity of unbroken stalks, however, can be advantageous from a technical point of view, since it facilitates the circulation of the must during the pressing and drainage process, redounding in enhanced extraction yields.

Once the crushing, and when appropriate de-stemming, process has come to an end the resulting paste is transported, together with the released must, to the extraction system where pressure is applied in order to obtain more must. The amount of pressure applied is a key factor in the process, as during pressing different compositions of must are obtained according to the amount of pressure applied: that referred to as "primera yema" must (approximately 65% of the total volume), obtained with pressures of up to 2 kg/cm2: the "segunda yema" must (approximately 23%), obtained with a pressure of up to 4 kg/cm2 and, finally, that known as "mosto prensa" which is produced by applying a pressure of over 6 kg/cm2.

Whilst the particular analytical characteristics of primera yema must make it suitable for biological ageing, segunda yema must whose structure derives to a greater extent from solids is used to produce wines better suited to oxidative or physico-chemical ageing.

The Regulations of the Denomination of Origin governing extraction methods state that only those musts obtained from a maximum yield of 70 litres for each 100kg of grape may be used to produce Sherry Wine. The rest of the must obtained by higher levels of pressure may be used to produce other, non-classified, wines, for the production of wine for distillation or to obtain other sub-products.

Newly extracted must is prepared or cleaned before fermentation in order to prevent oxidation and bacterial contamination, as well as to improve the aromatic finesse of the must once fermented. After filtration the clear the must is subjected to a process of pH correction by adding tartaric acid. This helps to prevent bacterial contamination during fermentation and to obtain healthy, balanced wines suitable for ageing.

Once the pH has been corrected the must is treated with sulphur dioxide in doses which vary from between 60 to 100 milligrams per litre, depending upon the condition of the harvested grapes, to prevent oxidation and possible bacterial contamination. The sulphur is generally administered in the form of gas injected directly into the circulation pipes. The must is then cleaned by means of a decanting, or racking process known as "desfangado" (Spanish for de-mudding). The clarified, solid-free musts are then transferred to fermentation tanks.

In general terms, alcoholic fermentation is a natural biochemical process by means of which the sugar contained in the grape juice - basically glucose and fructose - is transformed into alcohol. This transformation is possible thanks to the action of a fermenting agent: yeast. In addition to alcohol the transformation of the sugar produces large quantities of carbon dioxide, generating heat which raises the temperature of must in fermentation.

C6H12O6 2CH3CH2OH + CO2 + Q

The start of fermentation is normally instigated by means of what are known as "pies de cuba". Once the musts have been cleaned by the de-mudding process and are in the fermentation tanks, must already in full fermentation is added to the clear must in a proportion that varies between 2 and 10% of the total volume of liquid. This speeds up the start of fermentation and at the same time provides the opportunity to introduce a previously selected strain of yeast as a fermenting agent. Although the pie de cuba operation is sometimes carried out using spontaneous yeasts, more and more registered Denomination firms are opting to use indigenous yeasts selected to produce sherry wines of the best oenological and sensorial characteristics.

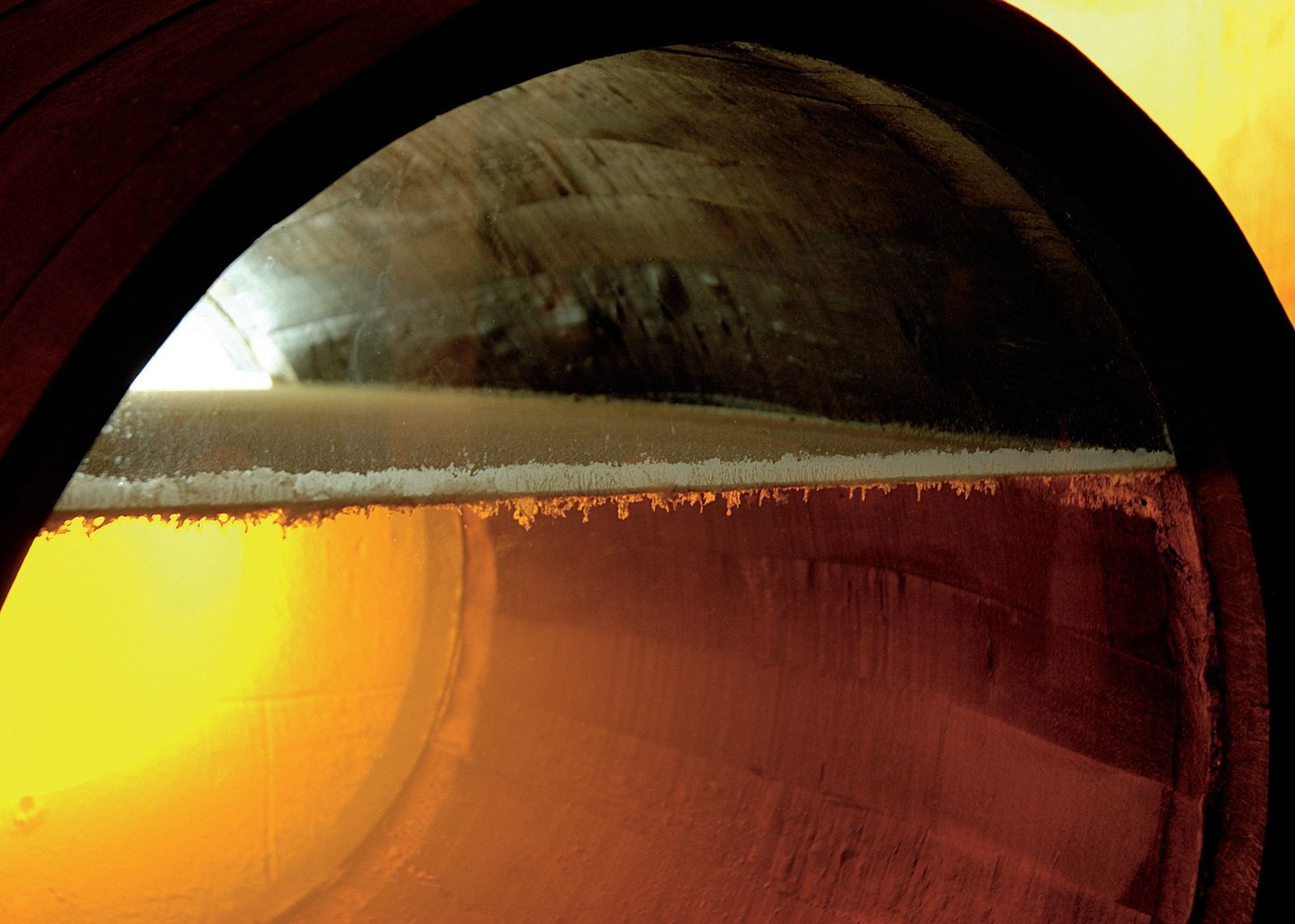

In general terms, complete fermentation can be divided into two different stages: a first phase know as tumultuous fermentation and a second known as slow fermentation. The duration of tumultuous fermentation varies according to the composition of the must and the temperature at which it is carried out. In the Jerez Region this operation is usually performed in huge stainless steel tanks with a capacity for 50,000 litres, in which it is possible to maintain the temperature of the fermenting must within recommended limits of between 23 and 25 degrees Centigrade. Within this temperature range yeasts develop much more comfortably, thus ensuring the total transformation of all sugar into alcohol. Nevertheless, some sherry firms still use the traditional system of fermentation in oak butts, or casks, their aim being to achieve a vinification of the must with specific characteristics.

After approximately seven days only a very small quantity of sugar remains in the must and the second, slow fermentation process begins which over the following weeks transforms the remaining final grams of sugar into alcohol, without the need for refrigeration.

Temperatures become increasingly milder as Autumn progresses, which favours the slow decanting of dead yeast and other solids in suspension known as dregs, or lees. As temperatures fall and the lees settle at the bottom of the tanks the fermented must gradually loses its initial cloudiness, gradually becoming cleaner and more transparent.

Towards the end of the Autumn the new wine of the year - known as "base wine" - is ready for the lees which have settled at the bottom of the tank to be separated and removed. In this way a completely dry white wine is obtained which is pale, delicate, slightly fruity and low in acidity which will constitute the base for the later production of Sherry Wines.

This is a young wine which during the months of January through to March is consumed in large quantities in the country inns and bars all over the Jerez Region and which is referred to simply as "must", or grape juice, despite the fact that its alcoholic content is of between 11 and 12% depending upon the conditions of the harvest.

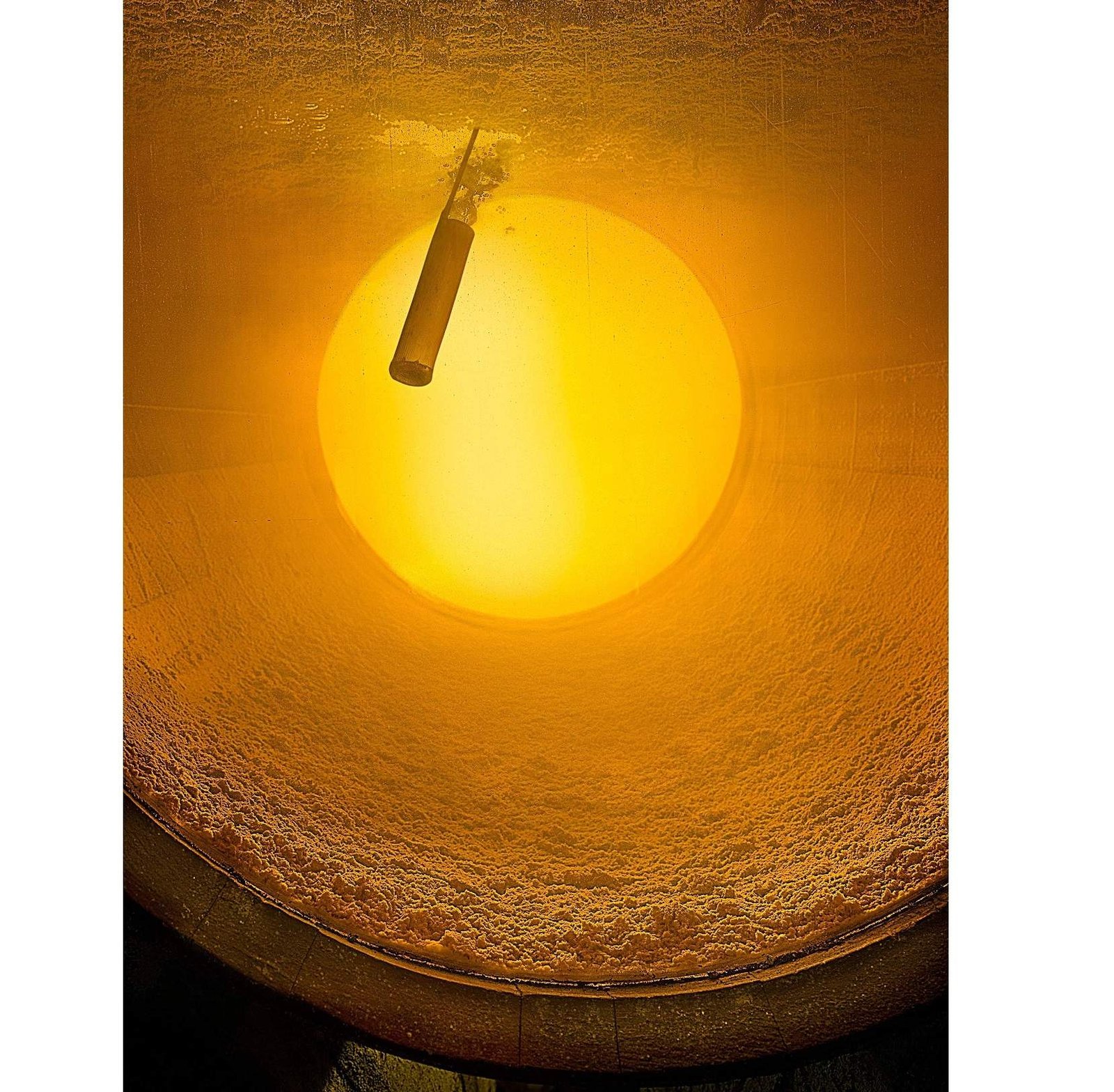

Once the lees have been removed we can observe a very special characteristic of the base wine: during the decanting process a film of yeast begins to form on the surface of the wine, a type of cream which gradually expands until it completely covers the whole surface: this is known as the flor.

The flor del vino is unquestionably the most extraordinary natural element of all those which combine to produce the uniquely characteristic Sherry Wines. If fermentative yeasts disappear as sugars are transformed into alcohol, then in the Jerez Region there is another strain of indigenous yeasts which carry on their activity even when all the fermentable sugars present in the must have been exhausted. Over the centuries, and undoubtedly as a consequence of natural selection, several strains of yeast have appeared which have learnt to feed off the alcohol created during fermentation in order to stay alive.

This film is not inert, but is in constant interaction with the wine. The living organisms which make up the flor, the yeasts, permanently consume specific components found in the wine, especially alcohol but also any remains of non-transformed sugar, glycerine, oxygen dissolved in the wine, etc... They also give rise to another series of components, most prominent amongst which are the acetaldehydes. In general terms, by their metabolic action they bring about significant changes in the components contained in the wine and therefore in its final organoleptic characteristics.

As with all living organisms, the yeasts responsible for the formation of the film of flor require a series of environmental conditions for their development. Temperature and humidity levels are of special importance: so much so that the very name of flor (flower) makes reference to the fact that the film of yeast appears to flourish, acquiring a particularly vigorous aspect in Spring and Autumn, times of the year which coincide with ideal environmental conditions of temperature and humidity.

As levels of alcohol in the new wine each their limit, these unusual yeasts form upon the free surface of the wine inside the butt where, with the help of oxygen from the air, they survive by metabolising part of the alcohol and other components contained in the wine.

The gradual reproduction of these micro-organisms produces a film-like culture of yeasts which covers the whole surface of the wine, in such a way as to prevent direct contact the air. The wine is thus totally protected from oxidation, totally covered by a natural layer of yeast.

The flor also requires access to oxygen in order to live. For this reason neither the tanks in which it first appears, nor the butts in which it develops, can be hermetically sealed as adequate air circulation must be ensured in the bodega at all times.

Finally, the existence of flor in the wine is only possible within a particular range of alcoholic strengths, which has very interesting consequences when the moment arrives for the cellar-master to decide which type of sherry wine he wishes to produce.

The vinification of those varieties destined for the production of sweet sherries is quite different from what we have seen so far regarding dry sherries.

Pedro Ximénez wines are produced exclusively from over-ripe grapes of the same name which are picked once they have attained a high concentration of sugar on the vine, in excess of 16 degrees Baumé (around 300 grams of sugar per litre of must). Once harvested the grapes are spread out on paseras, special sites set aside for drying out the fruit in the sun, a process known as "soleo", or sunning. The grapes lose a great deal of water during the sunning process, also known as pasificación (from the Spanish word for raisin: pasa), and consequently increase their sugar content (450-500 grams per litre of must). In parallel to this increase in sugar, other changes take place in the chemical, physical and sensory features of the dried, "raisined" grape: heightened colour, density, viscosity, stickiness and the emergence of aromas and flavours characteristic of Pedro Ximénez grapes and wines.

The practice of soleo consists in exposing the harvested bunches of grapes to the sun on mats of various shapes and materials, the most traditional being round redores, esparto grass mats. The grapes are carefully spread out by hand and turned over once a day to ensure that all the berries receive an equal amount of sunlight. During this operation, workers also remove unhealthy bunches - a practice known as espurgado (literally, purging or sanitising). In areas relatively close to the sea, the grapes are covered at night to prevent their being dampened by the typically heavy September dews. After several days, normally 7 to 15 depending on weather conditions (temperature and relative humidity), once the grapes are judged to have reached the optimal condition, they are collected and transported to the wine press for the next stage in the process, the extraction of must.

Given that the grapes are now dehydrated, pressing is rather more difficult than for newly picked grapes. As a rule, vertical presses are used and, to help in extracting the must - which is very dense and viscous owing to the high content of sugars and other substances in it - the grapes tend to be piled up in layers separated by the mats on which they were sunned. The texture of the esparto grass matting facilitates the drainage of must from the presses.

Once they reach the collection tanks, the musts are then submitted to a series of different processes according to their particular characteristics. Their high concentration of sugar affects spontaneous fermentation, which gets underway slowly. In order to stabilise fermentative microbiological activity in the musts, wine spirit is added to levels not far short of 10 degrees of alcohol. Thus stabilised the wine is left to settle during the autumn and winter months, after which the new wine is racked to remove any lees and further fortified up to 15 to 17 degrees of alcohol. The wine is then left to age in American oak casks, using the traditional añada and solera systems.

Moscatel wines are made exclusively from grapes of the Moscatel de Alejandría variety, which are harvested when very ripe. Moscatel grapes can also be sunned to obtain moscateles pasas. This is done in much the same way as for Pedro Ximénez though, mainly because Moscatel de Alejandría grapes are bigger, sunning dries them out less. Furthermore, since most Moscatel vines are found in sandy soil near the sea, the sunning process often takes place on paseras of sand.