The prevailing climate of the Jerez region is warm as a direct consequence of its low-lying latitude, it being one of the most southerly winegrowing regions in Europe (the town of Jerez sits on latitude 36º North). Summers in the region are dry and marked by high temperatures, thus provoking equally high levels of evapotranspiration, though the proximity of the Atlantic Ocean has an important role to play in maintaining levels of humidity and moderating temperatures, something that is more evident at night.

Spring and summer, the seasons which mark the growing cycle of the vine, are characterised by two prevailing winds known as the Poniente (from the west) and the Levante (from the south-east). The former is cool and humid (humidity levels can reach ninety-five percent), whilst the latter is hot and dry (with humidity levels of around thirty percent). The average annual temperature is 17.3ºC with very mild winters, during which temperatures rarely drop below zero, and very hot summers where temperatures frequently rise above 40ºC. The region enjoys a very high average of between 3,000 and 3,200 hours of effective sunlight.

Levels of rainfall are quite high, on average six hundred litres per square metre per year, usually falling in autumn and winter. With certain exceptions, this amount of water is sufficient for the correct evolution of the vines, supplemented as it is by the all important nocturnal humidity provided by the nearby Atlantic Ocean.

It should be noted, however, that the climate is not the same for all the vineyards of the region. There are marked climatic differences between the different sub-zones, districts and pagos which make up the sherry-growing area known as the Marco de Jerez.

The Sherry Region of Jerez is an area of open, gentle rolling hills or slightly sloping knolls - with gradients of between 10 and 15 per cent - covered by a limestone soil known as albariza, characterised by the extreme, dazzling whiteness it takes on during the dry months. This soft loam of chalk and clay comes to the surface on the tops of the hills, thus giving rise to the characteristic Sherry vineyard landscapes. It is rich in calcium carbonate (containing up to forty percent), clay and silica from the diatomite and radiolite shells present in the sea that once covered the region far back in the Oligocenic period. The finest albariza soil, with the highest proportion of limestone and elements of silica produces the most select and sought after sherry wines in the Marco de Jerez.

Its main characteristic from a wine-growing point of view is its high moisture retaining power, storing each winter's rainfall in order to nourish the vines during the dry months. Its leafy structure opens up like a sponge during the rainy season and absorbs immense quantities of water. Later the upper levels of soil bake hard under the heat of the summer, thus preventing the evapotranspiration produced by the region's high levels of sunlight.

Albariza soil is easy to work and, being very moisture retentive, facilitates an excellent distribution of the root system. Roots up to twelve metres in length have been found at depths of up to six metres in albariza soil.

Within the region there are also other types of soil used for the production of Sherry Wines, though in a lesser percentage, known as "barros" (clays) and "arenas" (sands). The former are predominant in lower-lying regions at the foot of hills and valleys. Sands are more commonly found in coastal areas.

The wine-growers of the region have traditionally divided the production zone into smaller areas known as "pagos": a term used to refer to small areas of vineyard delimited by topographical features and possessing homogeneous soils and mesoclimate. Famous pagos inlcude Carrascal, Marcharnudo, Añina, Bilbaina, etc... Up to 70 different pagos have been identified within the sherry region.

The Regulations of the Consejo Regulador indicate the following varieties of vine as being suitable for the production of Sherry: Palomino, Pedro Ximénez and Moscatel. All three are white-grape varieties.

The three varieties mentioned above, traditionally used throughout the Jerez Region, belong to the Vitis vinifera species, which gives grapes of the quality required to produce Sherry. The most widely favoured variety is that of the Palomino grape, together with others such as Pedro Ximénez, Mantuo, Albillo, Cañocazo, Perruno, Moscatel, etc... all of which were grown on their won rootstock. In the years 1894, however, destructive insect known as phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifolii) made its first appearance in Jerez and in many other parts of the world, the worst scourge in the history of viticulture which destroyed the vast majority of European vineyards by attacking the roots of the vine. The only possible solution was to plant American varieties of rootstock with phylloxera-resistant roots and then graft onto them the vines traditionally grown in the area. In such a way that the plant, from that period onwards, is always made up of a subterranean section (American rootstock) and an above-ground section, or vine stock, which produces the fruit. Both parts are joined at what is known as the graft union point.

Palomino is the most traditional of all varieties and has been used here for centuries. Nowadays it is the undisputable leader within the Jerez Region and, given its compatibility with the albariza soil, local climate and the techniques developed by vine growers; it may rightly be considered a key element in the production of our unique sherry wines.

The Palomino grape is known by several names, the most common being "Listán". It has an open apex and large, orbicular, dark-green leaves with a closed V-shaped petiolar sinus. The underside of the leaf is downy in texture. The shoots are semi-trailing. Grape bunches are generally long and cylindrical in shape with a medium to high density of spherical, medium sized, thin-skinned berries which are yellowish green in colour. The grapes are juicy, fragile, sweet and flavourful with colourless juice.

The buds of the sub-variety Palomino Fino - the most commonly used throughout the region - sprout during the last fortnight in March and ripen in early September. Yields are in the order of 80 hectolitres per hectare, registering around 11 degrees Baumé and low acidity. It is well adapted to the region, being highly resistant to a wide variety of parasites when cultivated correctly. The excellent quality of its grapes and its responsiveness in the vineyard make it the favourite among wine-makers and vine-growers alike.

Of much lesser importance is the sub-variety "Palomino de Jerez" which generally produces smaller yields with slightly higher levels of sugar and acidity.

This is another very traditional variety used throughout the Jerez Region, as indeed it is in other parts of Andalusia.

It is also known by the names Alamis y Pedro Ximén. Its greater sugar content (12.8º Baumé) and higher levels of acidity produce sweet wines of great quality. These grapes are generally submitted to a "sunning" process before they are vinified, with the aim of intensively concentrating the sugar content of the grape. Its fine leafage facilitates the process.

A variety used in the Jerez Region for the production of wines by the same name. The Moscatel wine produced in the region generally go under the name of "de Chipiona". Other names used are: Moscatel de Alejandría, Moscatel gordo, Moscatel de España, etc.

The variety originated in Africa, although it is now cultivated in many vine-growing regions throughout world, and there were already references made to it by Columela, writing in early Christian times. In the Jerez region it gives special sweet wines which bear its name, usually coming from "sunned" grapes of the highest quality. The vines of this variety are best suited to vineyards located close to the sea.

Apart from natural factors and varieties used, the way in which the vine is cultivated has a decisive effect both upon the yield of the vine and the characteristics of the grape produced. The vine-growing techniques used for making sherry have always had the historical distinction of being committed to quality in a very specific kind of wine, developing idiosyncratic practices which over the years have been adapted to current technological advances.

The vine-growers of the Jerez region exemplify the symbiotic relationship between man, plant and soil.

Preparatory work for planting is carried out in the summer, once the area in which the vineyard is to be planted has been selected, in an intense operation known as "agostado" (from the Spanish word for August). Ploughing up the land to a depth of 60cm oxygenates the albariza soil which is then manured as it is extremely poor in organic matter.

Once the land has been flattened, in December, the specific points where the each rootstock will be planted are clearly marked. These plantation marks indicate the distance at which each vine should be planted from the other. The traditional planting pattern used in the region used to be the "Marco Real" (a 1.50 x 1.50 metre grid). Due to the progressive mechanisation of the vineyards, however, a rectangular pattern with a 1.15 x 2.30 metre grid is now normally employed.

The rows of vines, or "liños", are planted from north to south in order to facilitate the maximum exposure to sunlight during the day, also taking into account the inclination of the land. On a vineyard in the Jerez Region the density of vines is usually of between 3,600 and 4,200 vines per hectare.

The phylloxera-resistant rootstock is planted during the winter in the form of a rooted vine shoot. In this way it is possible to take advantage of the winter rains which will later favour the correct development of the roots.

In addition to their logical resistance to phylloxera, the rootstocks used in the Jerez region must also possess another series of characteristics; especially that of also being resistant to limestone, given the high proportion to be found in albariza soil.

Once the rootstock has developed sufficiently during the spring-time, the months of August and September bring the grafting of the wine-root (generally Palomino). The bud grafting method is used, specifically the type commonly known as T-budding (escudete). A single Palomino bud along with part of the vine shoot from which it comes is inserted into the side of the rootstock just below the surface of the ground. The place where the bud is grafted is called a "cajuela". The scion is bound with raffia, leaving the bud free and the whole area is then covered with soil (a technique known as "aporca") to protect the graft.

The following spring the grafted area is uncovered and from that moment on the grafted bud begins to sprout, providing the origin for the upper part of the vine.

If for any motive the bud fails to sprout, then a new graft will be attempted the following winter, this time using the "espiga" method. As the stalk of the rootstock is now thicker, a transversal cut is made in order to insert a scion which is then wrapped in raffia.

Over the following three years the plant is pruned in order to direct the growth of the vine. The objective of this exercise is to enable the vine to reach a height suitable for its correct development, as well as to facilitate the different tasks which the vine will undergo once production begins. In the fourth year, once the ideal height of around 60cm has been attained, the two main branches which extend from the trunk of the vine then undergo production pruning. As systems are developed which allow for the progressive mechanisation of everyday vine-yard tasks, especially during the harvest, modern practice is to increase the height of the vine beyond what was traditional in the region.

The production of grape from the vine during these first years is usually of lesser quality and is used mostly for the production of wine-alcohol.

Production pruning must be carried out once the vine reaches maturity (as from its fourth year) in order to control yield. Pruning, which is carried out each year while the vine is at rest during the winter, consists in making certain incisions in the vine shoots and woody parts of the plant, ensuring that a number of buds, shoots and branches remain with a view to giving it shape.

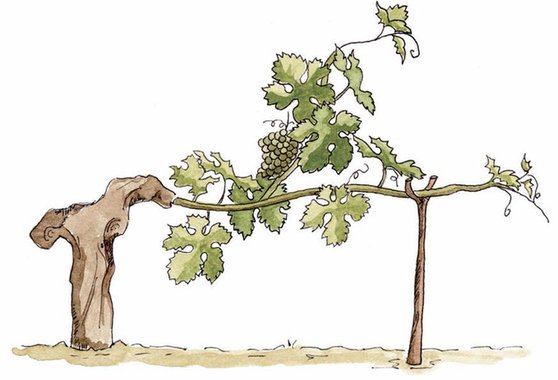

Pruning has a major impact upon the annual and vital development of the vine, which lives for approximately thirty years in this region. The production of each plant will vary according to the number of buds left on the vine after pruning, thus determining both the characteristics and quantity of fruit obtained. The type of pruning employed is therefore a relevant factor in wine-growing. In Jerez the predominant method is one known as "vara y pulgar" (stick and thumb) or jerezana: a traditional method of pruning specific to this Denomination consists of training each vine's trunk into two branches. These are pruned on alternate years leaving one long branch, or "stick", with at least eight or buds on it, whilst the other is pruned to a shorter shoot, or "thumb", with only one or two buds on it. The year's grapes develop on the on the longer "stick", whilst the buds on the shorter "thumb" sprout to form the following year's "stick", whilst this year's stick is then cut back to become a thumb once the grapes have been picked. Thus, each branch serves as a stick one year and as a thumb the next, successively alternating between the two from one year to the next.

The pruning cuts are carried out in a pre-established order, making cuts in both green and dry wood, known as carreras de verdes y de secos, in order to facilitate sap circulation and encourage both longevity and development in the vine. The carrera de secos corresponds to a series of incisions made each year during pruning, whilst the carrera de verdes corresponds to those sections of the vine left unscarred by these cuts.

To improve the shape of the vine and avoid later incisions which might cause scarring or the formation of unnecessary wood, additional light pruning operations, known as "castras", are carried out in spring to eliminate any superfluous branches that might compete with the productive branches of the vine.

Vines lined up in rows known as liños are today trained along espaliers made of two or more strands of wire to which the fruiting branches are tied and which support the vegetation. This must be exposed to the sun in order to allow the leaves to absorb the necessary amount of light for the plant to carry out the physiological processes required to produce quality grapes.

The ancient practice of tilling the land has two main objectives: in winter, helping the soil to retain and absorb as much rainwater as possible; in spring and summer helping it to retain its moisture content to ensure that the soil does not become parched under the blazing summer sun.

One of the tasks carried out on the albariza hillside during the winter in order to retain water is known as "aserpia" or "alumbra" and is specific to the region. It takes place after the harvest and involves building up ridges of earth between the vine rows to create a series of rectangular pits that serve to catch and store rainwater during the autumn and winter months, preventing it from running off and being lost down the hillside slopes. When spring arrives the aserpia channel walls are demolished and the topsoil broken up and levelled out.

Maintenance tasks from then on are geared to eliminating weeds, preserving moisture levels in the soil and preventing evaporation, which is of vital importance in the high summer temperatures.

The adjacent diagram shows the different viticultural tasks traditional to the Jerez Region, corresponding to a different stage in the annual growth cycle of the plant.